Nietzsche's adult life is bookended by questions of authorship attribution. At one end is what we now refer to as Homer and Classical Philology, Nietzsche's inaugural address delivered at the University of Basel on the 28th of May 1869. The lecture was originally entitled "Über die Persönlichkeit Homers [On the Personality of Homer]," which indicates how Nietzsche approached the question of authorship attribution. At the other end is the apocryphal My Sister and I, allegedly written in 1889 or early 1890 while Nietzsche was a patient in a Jena mental asylum. In between, he mentions the second most famous case of authorial attribution after the Homeric question, namely whether Bacon wrote the works we attribute to Shakespeare. In a notebook from the autumn of 1887, Nietzsche writes "this is perhaps the case with Shakespeare (provided that it really is Lord Bacon: - - -" (9[166]). A year later, he seems more convinced:

Is Hamlet understood? Not doubt, certainty is what drives one insane.—But one must be profound, an abyss, a philosopher to feel that way.—We are all afraid of truth. And let me confess it: I feel instinctively sure and certain that Lord Bacon was the the self...tormentor of this uncanniest kind of literature: what is tbe pitiable chatter of American flat- and muddle-heads to me? [Versteht man den Hamlet? Nicht der Zweifel, die Gewissheit ist das, was wahnsinnig macht… Aber dazu muss man tief, Abgrund, Philosoph sein, um so zu fühlen… Wir fürchten uns Alle vor der Wahrheit… Und, dass ich es bekenne: ich bin dessen instinktiv sicher und gewiss, dass Lord Bacon der Urheber, der Selbstthierquäler dieser unheimlichsten Art Litteratur ist: was geht mich das erbarmungswürdige Geschwätz amerikanischer Wirr- und Flachköpfe an?] (EH Clever 4)

A few sentences later, he concludes this section of Ecce Homo with this claim about his own authorship:

And damn it, my dear critics! Suppose I had published my Zarathustra under another name—for example, that of Richard Wagner—the acuteness [Scharfsinn] of two thousand years would not have been sufficient for anyone to guess [zu errathen] that the author of Human, All-Too-Human is the visionary of Zarathustra.

We can ask lots of questions here. I want to focus on one; namely, can we tell that Nietzsche is the author of both texts using stylometry? One reason I think that this might be helpful is that it will help us to be more objective. After all, we already know who wrote both texts, so it would be difficult to consider anything else a live possibility. By having a computer do the analysis, we at least make it easier to maintain our cognitive distance.

It might seem unfair to use cutting-edge algorithms to take up Nietzsche's challenge, two millenia or not. Although I will later use more up-to-date tools, here I want to begin with the birth of modern stylometry, which occurred in Nietzsche's lifetime. I won't apply the results here lest this already long post grow exponentially, but I plan to elsewhere and will update this once that is available.

The inception of modern stylometry is often cited as 18 August 1851,[1] a few months shy of Nietzsche's seventh birthday. On that date, Augustus De Morgan (the same De Morgan for whom the transformational rules in formal logic that permit the expression of conjunctions and disjunctions in terms of each other via negation are named) wrote to Reverend W. Heald suggesting that authors have characteristic mean word lengths when calculated to three decimal places. As he puts it: "one man writing on two different subjects agrees more nearly with himself than two different men writing on the same subject."[2] Nothing much came of this idea until 1887, five years after the letter was published. Thomas Mendenhall, an American physicist, took De Morgan's idea and coupled it with his experience with spectroscope and suggested that word length spectrums be graphed. The idea was simple enough. Along the x-axis would be word lengths, while the y-axis would represent the number of words of a particular length in the text in question. His idea was just as every element produces a characteristic spectrum, so, too, to do authors' works exhibit characteristic word-spectrums.[3]

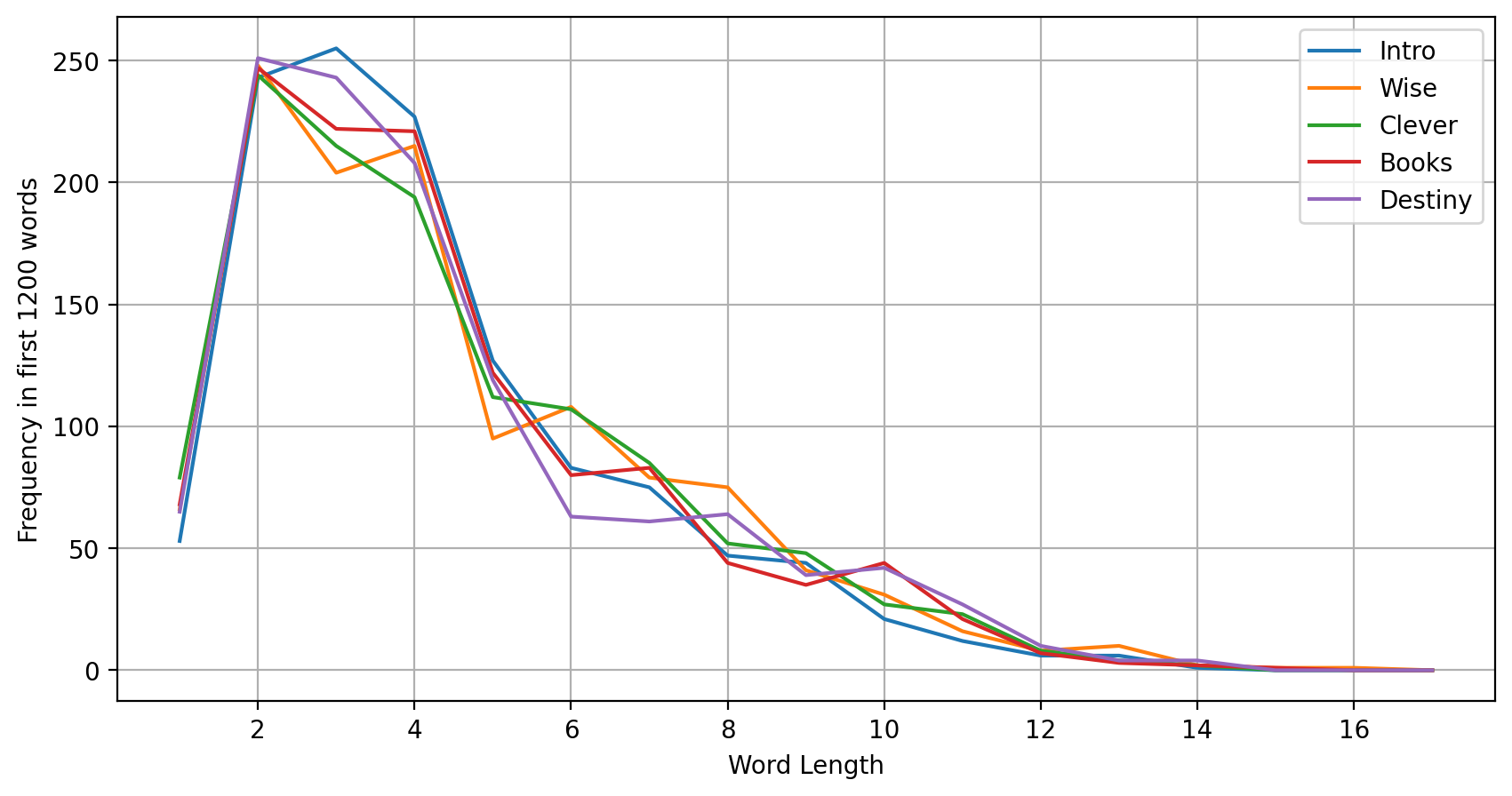

I began my exploration of this approach by comparing the five sections of Ecce Homo in English as a proof-of-concept. I also did this because part of Mendenhall's evidence for his hypothesis is his analysis of two speeches by the same person on the same topic, but aimed at very different audiences. He claims that “the two addresses 'read' very differently, but their diagrams are strikingly alike in their main feature.”[4] I expected the chapters of Ecce Homo to be all but identical, but the results don't bear that out:

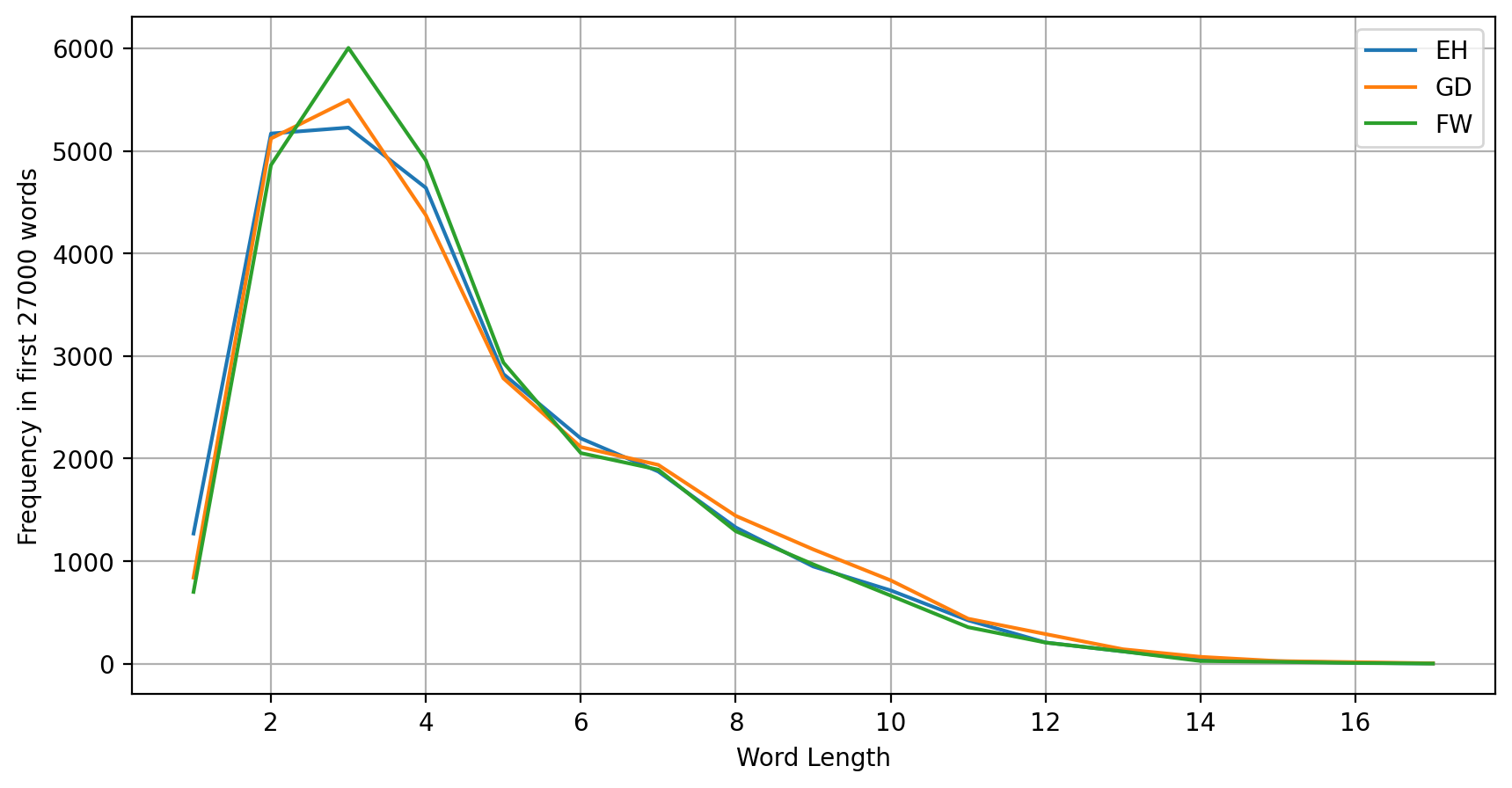

At the same time, they did seem minimally promising, and I was willing to grant that the small sample sizes did not work in Mendehall's favor. So I compared three complete books: Ecce Homo (EH), Twilight of the Idols (GD), and The Gay Science (FW). Again, I used English translations as they were more readily available to me.

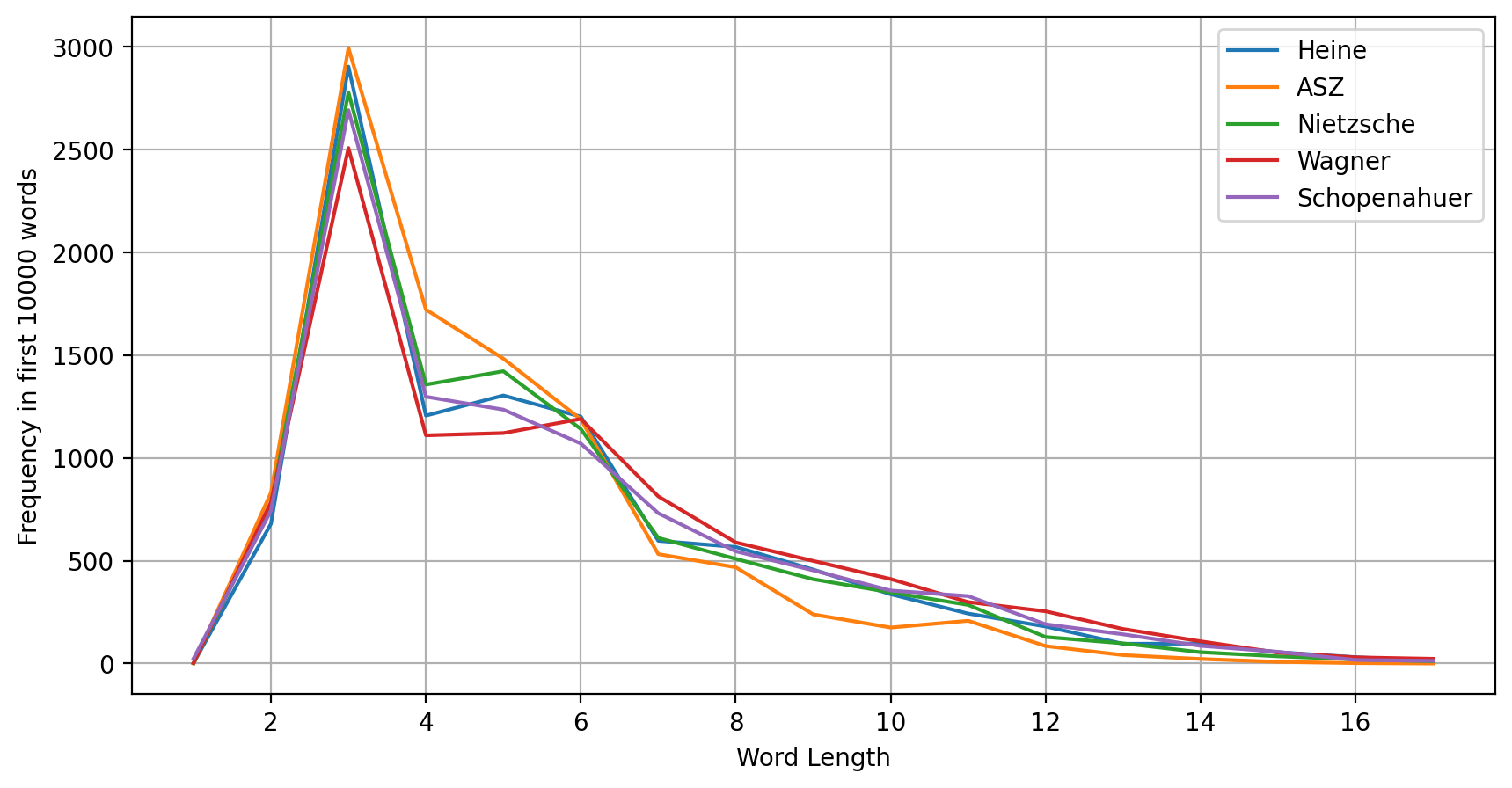

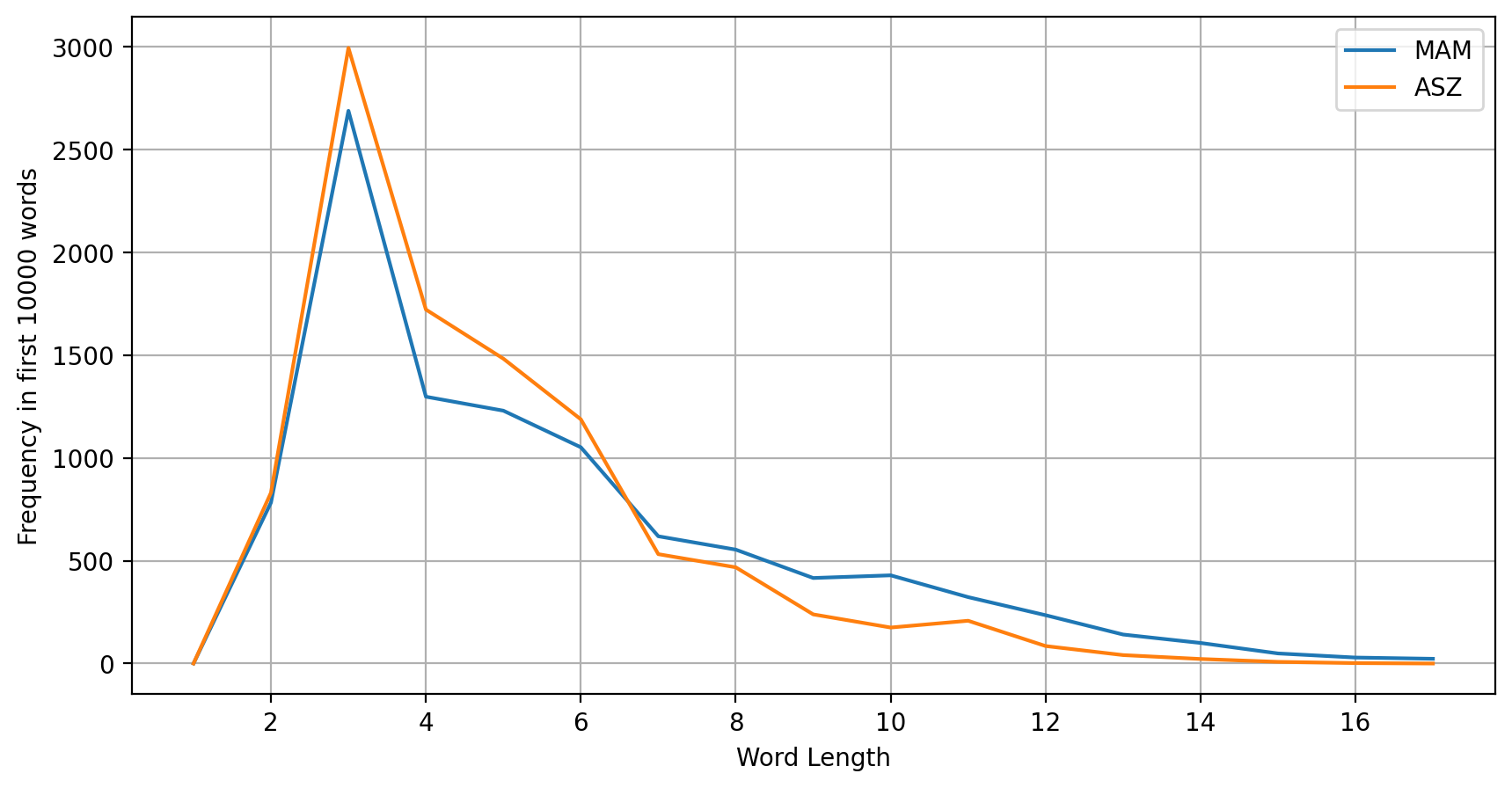

Other than The Gay Science's notable increase in three-letter words, the curves seemed identical. This gave me the confidence in this approach to try comparing several authors in German. Authorial attribute cases are classified as closed or open, depending on whether there are a fixed number of possibilities. For example, "Did Bacon write the works we attribute to Shakespeare?" would be closed, while "Who wrote the works we attribute to Shakespeare?" would be open. In one sense, this isn't really either kind of question since we know who wrote Thus Spoke Zarathustra. I chose to consider this a closed set question (i.e., Could Wagner have written AZS?). In such cases, it is generally recommended to include several distractor authors or impostors. To keep the quality of the sources as equal as possible, I attempted to use files from Project Gutenberg only. Of the possible distractors, I chose Heine and Schopenhauer as being sufficiently similar to Nietzsche and Wagner. Unfortunately, the only work by Wagner available in German from Project Gutenberg was the libretto for Der Fliegende Holländer, which is too short compared with the other texts used. In its place, I used a scan digitized by Google of Wagner's Mein Leben, which required substantial cleaning to bring it line with the Gutenberg files. The other works used were:

- ASZ = Also sprach Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen (Gutenberg source).

- Heine = Die Harzreise, Das Lied vom blöden Ritter, and Almansor (Gutenberg source, Gutenberg source, and Gutenberg source).

- Nietzsche = Menschliches, Allzumenschliches and Ecce Homo (Gutenberg source and Gutenberg source).

- Schopenhauer = Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit (Gutenberg source).

Aside from removing English text, no cleaning was done to these files.

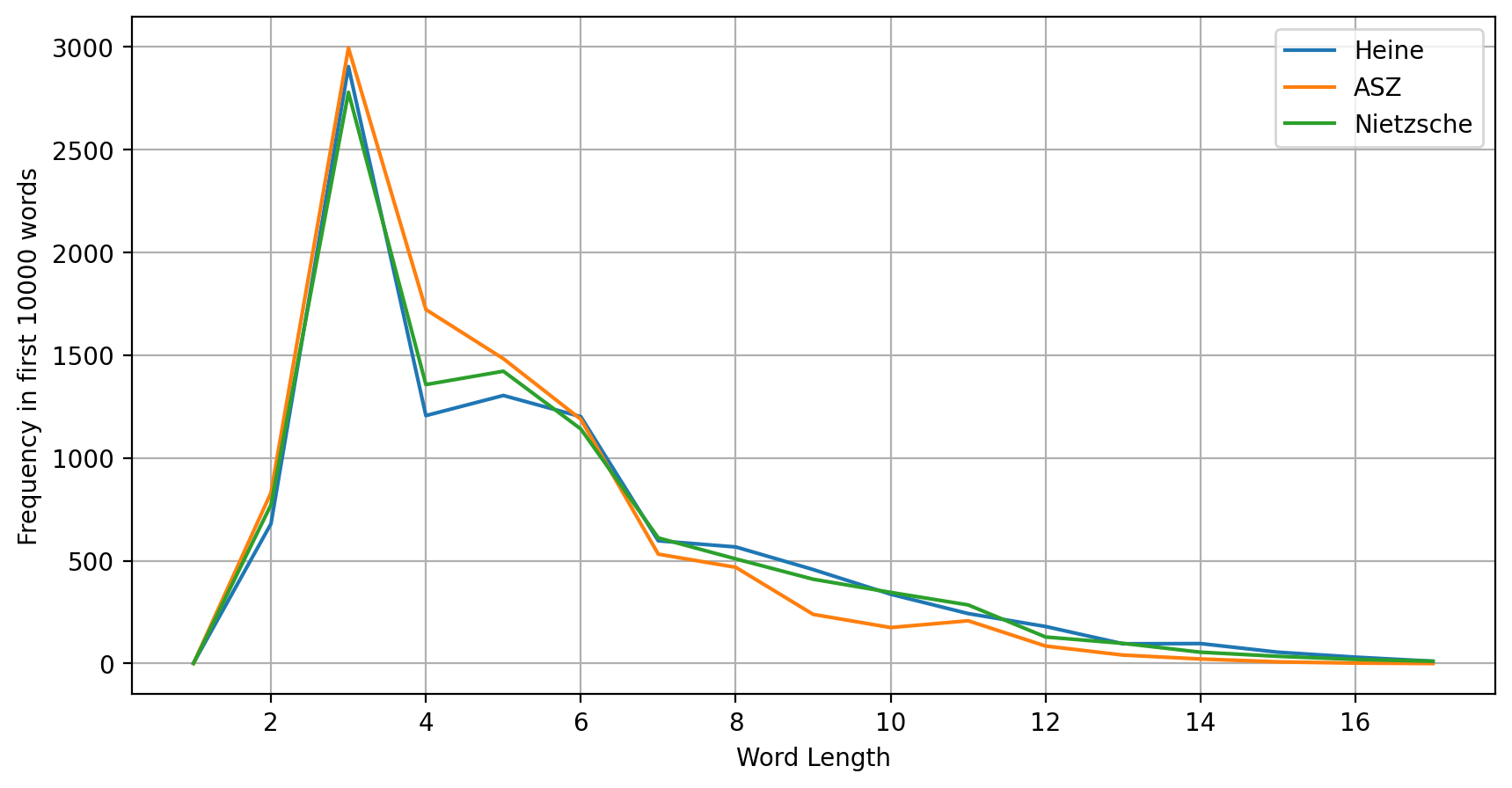

Of all the potential authors of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Wagner seems the least likely. His usage of 3, 4, and 5 letter words is notably less than the other authors. Everyone except for Schopenhauer converges on their usage of six letter words. After that, Wagner uses longer words than the other authors, especially the pretended unknown author of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. If we eliminate Wagner as the author of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Schopenhauer would be the next to be eliminated. Removing the two of them from contention produces this graph:

Heine and Nietzsche are closer to each other from Mendenhall's perspective than either is to the author of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. If nothing else, this helps us to appreciate better why Nietzsche would predict that "One day it will be said that Heine and I have been by far the foremost artists of the German language" (EH Clever 4).

Lastly, we can look at the challenge that Nietzsche poses: can we tell that Human, All-Too-Human and Thus Spoke Zarathustra were written by the same person? The graph below suggests not. The earlier work favors words of seven or more letters, while Zarathustra has more shorter words.

Conclusion

Depending on what we take Nietzsche to be asking, we seem to have some answers. We can tell that Thus Spoke Zarathustra was probably not written by Wagner. But I think we would be hard-pressed to show that it was written by Nietzsche rather than by Heine. Could we tell that it was written by the same author as Human, All-Too-Human? That seems unlikely. If anything, the evidence suggests that it wasn't. Presumably Nietzsche's point is that his intellectual growth essentially made him a different thinker. Of course no stylometric analysis can offer any guidance as to whether the change was good or bad.

There is a certain paradox in these results. If Mendehall's approach is viable, then Nietzsche is correct about the change in his writing. But given that both works were written by Nietzsche, his case counts against the foundational assumption of stylometry; in which case Mendenhall's approach—as well as all other stylometric techniques—are based on a faulty assumption. The simplest way out of this predicament is to see whether Mendenhall's approach is accurate.

A little more than a century after Mendenhall published his results, a researcher argued that “Mendenhall's method now appears to be so unreliable that any serious student of authorship should discard it."[5] Although a harsh assertion, it is unclear to me why Mendenhall's approach ever seemed viable. Stylometry rests on the assumption that, as one researcher puts it, "authors have an unconscious aspect to their style, an aspect which cannot consciously be manipulated but which possesses features which are quantifiable and which may be distinctive.”[6] While I am sympathetic to that assumption, I am unaware of any explanation of the mechanism by which we unconsciously—or even consciously—attend to word length. Word games aside, it does not seem that we generally know how long the words are that we use. Moreover, since letters vary in their widths in normal circumstances, there would not be any visual indication that we might pick up on.

About the code

The code was written in Python running in a Jupyter notebook. The tokenization was done with spaCy and the graphs with Matplotlib. Word lengths greater than seventeen are not displayed because they are dimishingly few and because displaying them would have made the charts unwieldy. The code is available on Github here.

References

[1] Richard Bailey (1969), "Statistics and Style: A Historical Survey" in Statistics and Style. Lubomír Doležel and Richard Bailey, eds. P. 217. Also see Holmes, D. I. (1998). "The Evolution of Stylometry in Humanities Scholarship." Literary and Linguistic Computing, 13(3), 111-117 (112).↩

[2] Sophia Elizabeth De Morgan (2010[1882]). Memoir of Augustus De Morgan With Selections from His Letters, p. 216.↩

[3] Thomas C. Mendenhall (1887). "The Characteristic Curves of Composition," Science, ns-9: 214S, pp. 237-246.↩

[4] Mendenhall, T. C. (1901). "A Mechanical Solution of a Literary Problem." Popular Science Monthly, 60, 97-105. ↩

[5] Smith, M. W. (1983). "Recent experience and new developments of methods for the determination of authorship." Association for Literary and Linguistic Computing Bulletin, 11(3), 73-82. ↩

[6] Holmes, D. I. (1998). "The Evolution of Stylometry in Humanities Scholarship." Literary and Linguistic Computing, 13(3), 111-117 (111).↩